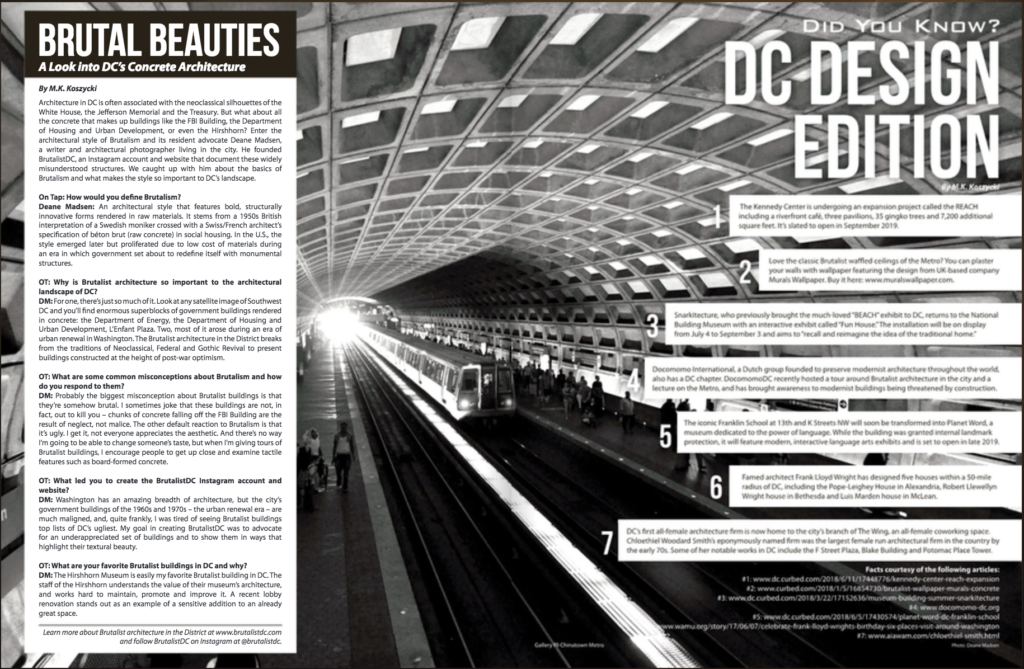

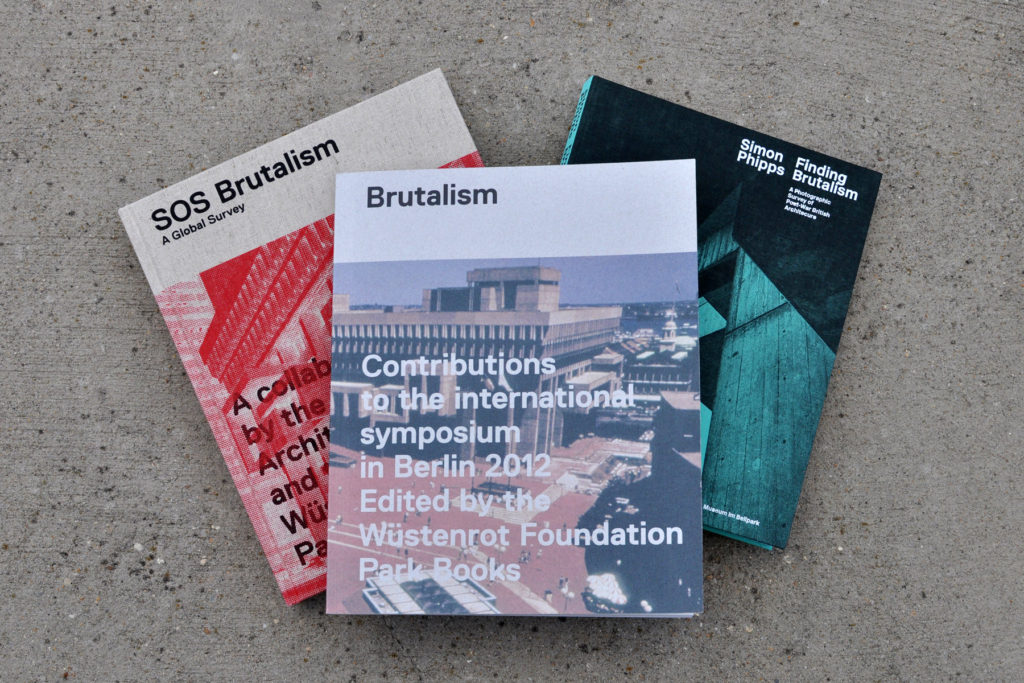

Here at BrutalistDC headquarters, we have several shelves dedicated to all matters concrete, and have had to make room for the many new editions that have been arriving at a steady pace for the last few years. Two of the latest, “Finding Brutalism” and “SOS Brutalism,” (both from University of Chicago Press and Park Books) offer new looks at the style. BrutalistDC founder Deane Madsen reviewed them for Architectural Record:

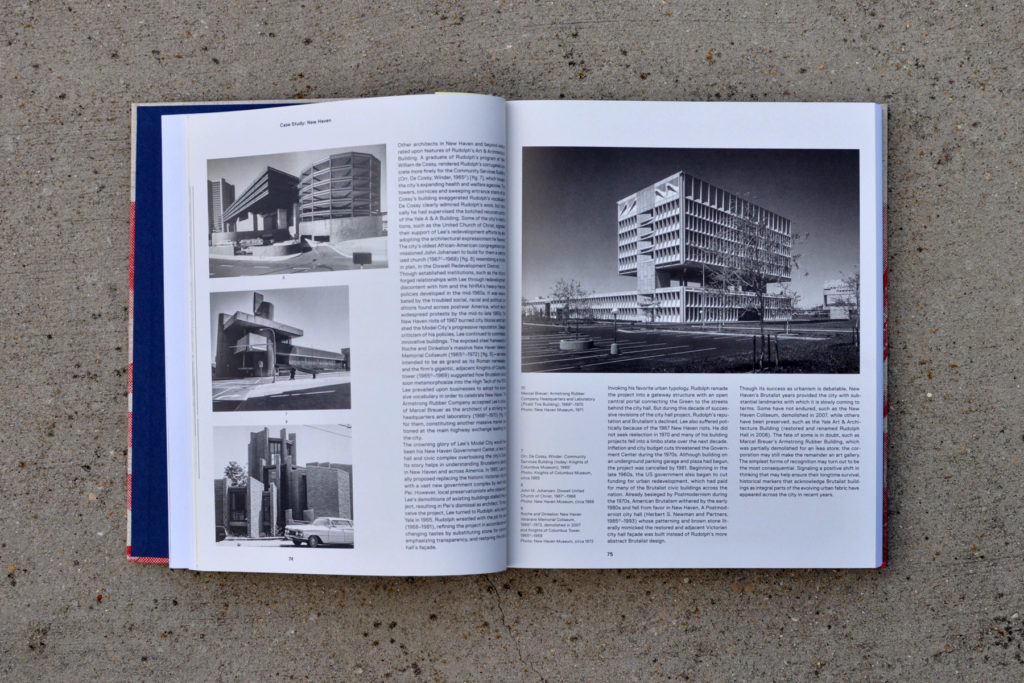

SOS Brutalism presents the theoretical issues behind the term in a two-volume set covering the origins, current state, and potential future of Brutalism. The eponymous first volume is a worldwide compendium—based on the website #SOSBrutalism—that has more than 1,100 Brutalist buildings in its database.

This effort is filled with case studies and examples of structures of varying status: still in use (such as Minoru Yamasaki’s Shiraz University in Iran), heritage-protected, under threat of elimination, or demolished. Chapter introductions show the divergent attitudes to each region’s embrace of the movement. The companion volume, Brutalism: Contributions to the International Symposium in Berlin 2012, comprises 17 lectures in which authors investigate theories and regions where Brutalism was practiced according to country-specific interpretations.

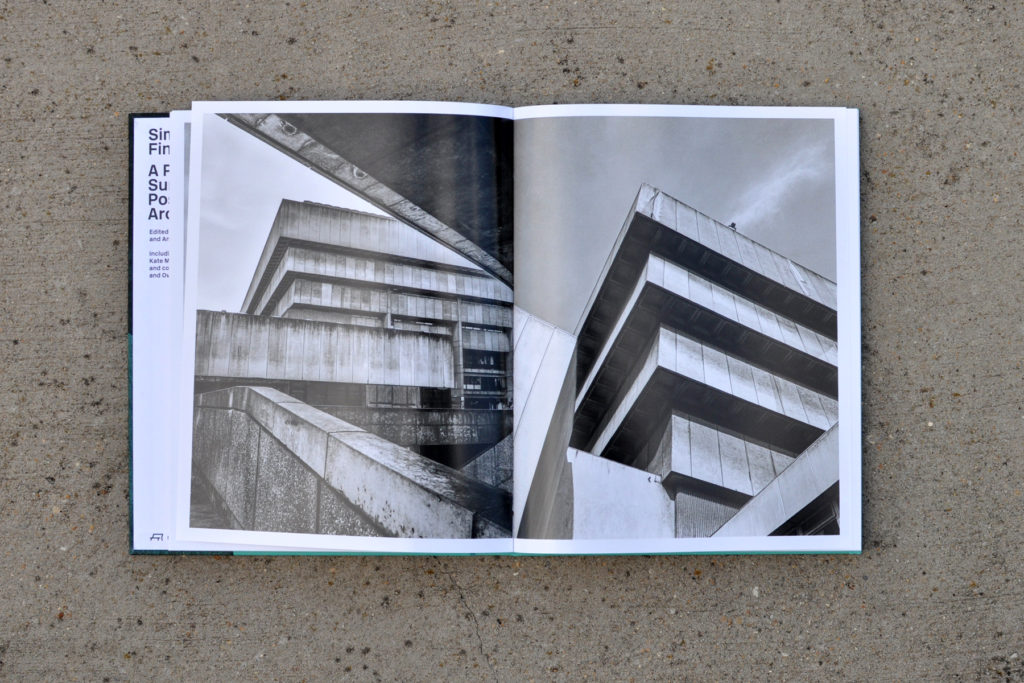

In Finding Brutalism, Simon Phipps lets a rich assortment of his black-and-white photographs do the talking, save for a trio of essays at the back. But that’s precisely the point: each of his images is a 1,000-word composition on material, scale, or form, and Phipps is a master storyteller in this medium without “the distractions and extraneous detail of color,” so, as he writes, “the form and structure and surface textures [can] be amplified by the action of light and shadow.” His approach returns to the origins: “The biggest misunderstanding about Brutalism is that it is all about concrete—not only concrete, but massively formed concrete. The essence of Brutalism for me is material ‘as found.’ ”

Read the full story at Architectural Record.